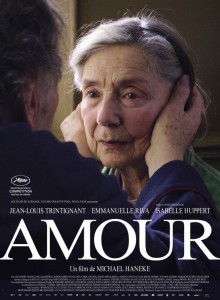

by Antoinette Weil

PLEASE NOTE: This post contains spoilers.

If the emotional response evoked by a film is any measure of greatness, then Amour wins.

After seeing the film, I cried most of the car ride home from the theatre, and then once in the bathroom when I got home. My eyes are welling up right now thinking about it. I am so incredibly sad.

I was thinking, with the title being Amour, that I might see more of a traditional love story, albeit a senior citizen love story. I thought perhaps the suffering of one would bring them closer together, they’d fall more deeply in love, “still the one”, all that jazz. But this was a different kind of love story.

Amour shows us the depth, the brutality and beauty, of a love that has withstood time and joy and pain and just about everything in between. Both terrifying and admirable, this portrayal is perceptive and sincere.

Amour follows husband and wife, Anne (played compellingly by Emmanuelle Riva) and Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant), through their struggle with Anne’s deteriorating health. She goes slowly, first suffering one stroke that leaves the right side of her body paralyzed. Wheel-chair bound and utterly vulnerable, she needs Georges’ help for the most basic tasks like washing her hair, pulling up her pants after going to the bathroom, or getting in and out of bed.

While Georges is out attending a funeral one rainy afternoon, Anne tries to kill herself by jumping out of the courtyard window of their apartment. When George walks in earlier than expected and finds her, she shrugs that she was only sorry that she was too slow. She very seriously tells him that she doesn’t want to live any longer, doesn’t want to wait around for things to get worse. But she lives, and they do.

The second stroke leaves Anne completely helpless and utterly unrecognizable from the person she once was. Unable to speak or move on her own, Ann continues down the slope. And Georges stays the course, stating “Things will go on, and then one day it will all be over.”

The movie caused me a cascading pendulum of emotions that swung from benevolent sympathy to gut-wrenching depression. At one point I recall thinking to myself in the theater I could have gone my whole life without seeing this movie. And been happier for it.

I’m not unhappy that I saw the film. But the aftermath is severe and I think the feelings that the film has left me with will be long-lasting, or at the very least, will again well up inside of me when I recount the experience. Michael Haneke, Amour’s writer and director, must have known what he was doing.

In one scene, Georges tells an anecdote about a film he had seen as a boy that touched him so deeply that he found himself distraught afterward and ended up crying in front of the first person who asked him about the movie.

Georges: I started to tell him the story of the movie, and as I did, all the emotion came back. I didn’t want to cry in front of the boy, but it was impossible; there I was, crying out loud in the courtyard, and I told him the whole drama to the bitter end.

Anne: So? How did he react?

Georges: No idea. He probably found it amusing. I don’t remember. I don’t remember the film either. But I remember the feeling. That I was ashamed of crying, but that telling him the story made all my feelings and tears come back, almost more powerfully than when I was actually watching the film, and that I just couldn’t stop.

Yeah, I see what you did there. Projecting exactly what’s going to happen to me once I am finished watching your film. Well played, Haneke.

The struggles that these two characters face—the humiliation, the power-shift of extreme dependence and responsibility, losing a partner, and facing death head on—are intensely painful and difficult to watch. But that’s not what makes it so hard, and it’s not what makes this movie so emotional.

We, the audience, we’re not crying over Anne and Georges. We’re crying over our grandmothers and grandfathers who we watched lose mobility and shrivel down to half-size and suffer the confusion and maddening frustration of not knowing who they are. We’re crying thinking about our parents falling ill, the hard decisions we’d have to make, and whether we’d make the right ones. We’re crying about the prospect of being so completely dependent on others, of someday not having control over our own bodies, our own minds. We’re crying over the time we should have spent with the people who are gone when they were still around. We’re crying, during Amour, about the terrifying prospect that we’ll be Anne or Georges one day.

And just like the film that afflicted George so profoundly, this film will stick with you long after you’ve exited the theater.